- Home

- Lauren Elkin

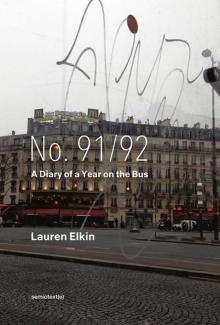

No. 91/92 Page 4

No. 91/92 Read online

Page 4

05/15/15

Friday afternoon

Gave the exam to my other class. On my way home I have to get off the bus and sit on a bench. Feels like parts of me are touching parts they're not supposed to.

05/15/15

Friday night

Meeting M for dinner I venture a metro poem, after Jacques Jouet, though I am no poet. What you do is you think of a line when the train is between stations, and hastily jot it down when the train stops. If you change lines, you make a new stanza.

I'm on the mend and on the tube.

An outlier not an inlier, out of place, tubular.

A man with a red leather handbag, a tote, beautiful, sharp against his white collared shirt, his grey sweater, his black slacks, his black hair, white repettos.

The bag on the man as out of place as an embryo in a tube, who's to say what's in place on a man.

Or where an embryo should be for that matter.

On the Internet the women claim conspiracy, accuse the drug companies, they want to sell more methotrexate, surely in this day and age they could move it into the right place.

Distract with thoughts of summertime, on its way, metro posters, 1 trait d’eau gazeuse 2 volumes d’aperol 3 volumes de prosecco and they don't mention the massive olive or the orange wheel.

Stabbed on a stick and thrust into your drink, in the summertime. Imagine amputating the grand canal.

You'd be left with no way to get from one place to another, a stranded egg; make your home in some tube.

05/20/15

Wednesday morning

Waiting for the 64, Gambetta to the library. At the bus stop a pregnant woman who must almost be due has to thrust her stomach in my face before I notice her; I am too busy recounting to my pregnant friend J how I've been doing, psychologically, since the surgery, and then that stomach in my face. Oh sorry, I didn't see you, I stand up, resentful, thinking I could be pregnant too for all she knows, and then where would we be? but of course the biggest bump gets the seat. Some consolation in thinking that even if I hadn't lost the baby I'd still be standing. But not much. Fuck thefucking pregnant woman I mutter to my friend who knows not to take it the wrong way. fuck you fuck all pregnant women.

05/21/15

Thursday afternoon

64 back to Gambetta. Across from me, a man plays the bongos on his backpack. He's not bad. Check my email. Your baby is now the size of a grape! I really need to cancel this subscription. But I can't just yet. I'd rather think about my baby growing over the next week to the size of a kumquat. I'd rather think about that.

I'm hungry but embarrassed to eat, this isn't the time or the place, you don't eat on the bus, I'm getting a headache, but if I eat someone will sarcastically say to me bon appétit. I don't care I don't care I don't care stop trying to flatter strangers eat your stupid crunchy sesame bar that you bought three months ago the one you keep in your bag in case you get hungry, well you're hungry now, write what you want, do what you want, cause you're hungry and you've given up caring what anyone thinks and isn't that the best way to write, let alone live? Let alone love.

No. 11/8

Monday 11/16/15

It's a few months later, and I'm a metro commuter now. Today's a bad day. Total crush. My boobs on some girl's arm, my arm in some guy's groin, an orgy of commuters. A bit of fluff escapes from behind my ear and drifts down in front of my face. It tickles my nose and I try to welcome the sensation instead of fighting it. We travel, groping each other blindly, all of us enduring.

The spring was spotted with deaths and near-deaths; the loss of my pregnancy, then the death of my mentor, then almost my dog, and finally a woman I never met but spoke to a lot on Facebook. I went to her funeral in the crematorium at Père Lachaise, and stood and cried with her family and friends, feeling like even though I didn't know any of them, I was in the right place, it was the right place to go that day.

The puffy scars from my surgery stood out against my skin, and slowly flattened, and the year got even worse.

The metro is an exercise in closeness that feels unbearable right now. All of us locked up together in a small space thinking of the same thing. I look over my shoulder and there's a woman in the seat behind me reading about the attacks. Longest night of his life, goes the headline above a picture of François Hollande. Rational friends of mine are avoiding the metro at rush hour. A friend who's late to meet me tells me he got off the metro a few stops too soon because he didn't like the look of a guy. We're all jumpy.

A man goes to the ground with his bag and we all look at him. It's awful that our first thought isn't is he ok, but is he going to try to kill us all? How easy it would be to hide an explosive vest under a puffer jacket, its wire disguised as a white headphone cord, the activation device as an iPhone. These are the things we're thinking about, wondering if headphones are explosive devices. We're all in this together but who can we trust?

I've started having panic attacks on the metro. I have to get off a few stops early and walk home.

But I realized the attacks are coming not in the beginning or the middle of the journey, but just as I'm about to get off. I'm not afraid of the train, I'm afraid of the destination. What are we heading towards, stop by stop? What's just down the track? It's enough to make you want to walk everywhere. Slow it all down. Even if we're not safe on the streets we can go at our own pace.

I find myself looking at the other people in the city with a new care. They're no longer people in my way. I would feel badly if one of you got hurt. I would hurt if you were hurt. I'm sure some of the people who died took this bus, took this train. Sat where I'm sitting. This strapontin. This one. And that one. I wonder how many times I've been on a bus, or on the metro, with any of them. The chances are good.

Ah Paris I want to make it all better, smooth your rumpled pavement, kiss the hot forehead of Sacré-Coeur.

We're going to have to get used to taking the metro again, though it feels so risky, and brings us into a painful proximity. But it's the closeness that will help us through. We're all repeating to ourselves that the chances of it happening to us are very slim. This is a terrible way to live in a community together—hoping that if the worst strikes, it strikes someone else.

In the city we are forever brushing sleeves with our other possible selves. Underground we go shooting through the tunnels trying to survive and be happy. So many books and films about cities take this as their premise: What if we'd made that train we missed by a second? Are we passing our soul mates on the tracks, in the train going the other way? We're learning this in a new way, after the attacks. If we'd had dinner in one place, instead of another. If we'd gone to see that gig, instead of the other. But what if we could turn this fear into the thing that gets us through this terrible time? We pass people in the street every day and we may not meet them for years, if ever. But we might one day—you just never know. And this must be at least one of the most potent meanings of community: potentiality.

A few days before all this happened, I was once again teaching Georges Perec's strange little book An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris (1974) in which he records spending three days sitting in the Place Saint-Sulpice trying to write down everything he sees around him—which buses go by, what kinds of cars, what the people and birds are doing, what the cafes are serving, who's drinking which wine with lunch, what the street signs say, if there are nuns, who's carrying a shopping bag, a plank, a crate, etc. It's a poignant inventory of a Paris of the past (before we all filled up every spare moment gazing into the glowing oracles in our hands), full of 2CV cars and tourists with actual cameras instead of phones on selfie sticks. It's also an exercise in noting what Perec can't see, what's just outside his peripheral vision, threatening to undo the whole; “even when my only goal is just to observe,” he writes (in Marc Lowenthal's translation); “I don't see what takes place a few meters from me: I don't notice, for example, that cars are parking.” There is so much we miss; none of us can have a total visio

n, or total understanding, of even just one place in our cities. This is a powerful and humbling thing to be aware of. As a member of the Oulipo— the Workshop of Potential Literature—Perec valued the potential almost above the actual.

But the reason I keep thinking of Perec is because of another essay he wrote the year before that, called “Approaches to What?,” in which he argues that as a culture, we are preoccupied by the “big event, the untoward, the extra-ordinary”; the daily newspapers are full of plane crashes and car crashes and tragedies, and totally ignore the daily—the everyday, what Perec calls the “infra-ordinary.” The attempt to exhaust a place in Paris is an act of cataloguing that is destined to fail, yet what matters is not the importance of what is observed, but its triviality. The very futility of asking such questions, he writes, is “exactly what makes them just as essential, if not more so, as all the other questions by which we've tried in vain to lay hold on our truth.”

The infra-ordinary. The bus, the metro, the Velib. Everyday ways of getting here and there.

I often teach Raymond Queneau's epic Exercices de Style (1947) in creative writing workshops, this amazing book of 99 different ways to tell the story of a guy on the bus. Queneau, Perec, Roubaud—Oulipians are never so happy as when they're on the bus. And we read their bus stories because they teach us how to live together, they teach us our daily encounters are a hundred thousand billion different stories told by Parisians over dinner. And their love of the daily, the zany, the things you think of when you're busy doing other things, that's what gets you through. Queneau wrote that book just three years after Paris was liberated from the Nazis. That's not a very long time.

Since that night, all of us here in Paris, and many people abroad, have been asking what feel like futile questions, as we try to grasp someone else's perverted idea of truth. Why did they do this, why those places, why those people? Might it all happen again? When? Where? How can we avoid this? How can we be safer in our city? Beyond the air strikes that have already started, beyond the think pieces that encase the events, beyond the catastrophe-comparing and victim-blaming that's already flying fast and loose, the answers are eluding us.

Someone wrote somewhere—maybe it was Virginia Woolf?— that peace is only possible when one man holding a gun can imagine that the other man he's facing down, who is also holding a gun, is a human being like he is, with a family who loves him. (I thought it might be in “Thoughts on Peace in an Air Raid,” which I've just reread, looking for it. It isn't.)

Whoever said that, and someone definitely has, I think what they meant is that peace is only possible when both sides acknowledge the enemy's right to an everyday, to the infra-ordinary. And what happened on Friday night was an amputation of that right.

It's the everydayness of the attacks that gets me, that puts up the block I can't think through, or around. These people, they bought those clothes they were wearing, and paid with their bank cards, and had bankers who will close out their accounts, they had electricity bills, they had shaved that day, or not, and they had pimples, and they were coming down with something, and they'd had a fight, and they were watching their weight, and they'd just got the new album, or they wanted to leave early, or they were watching their weight, and some of them had probably made a note to call the vet on Monday because the dog's vaccinations were up, because some of them had pets, just as they all had parents, siblings, friends, teachers, bakers, people to miss them and mourn them, and also neighbors, like us, who didn't know them, who may not know they're specifically gone, who only know that some group of people we've never met stopped living on Friday, while we're still out here, and all we can do is keep doing every day.

Paris is not a ghost town, in spite of what they're saying on the American news. Since the morning after, people (at least in my neighborhood of Belleville) have been out and about, doing the kinds of things Perec noticed in 1974: buying food, drinking in cafes, carrying shopping bags, even (as we did) carrying a digital piano with its pedals and stand half a mile for a friend. We're defiant, but shaky. We can't get over what we've seen, what we've heard, who we've lost, and we don't really want to. But we'll eventually get used to the fact that it happened. It will become part of our daily lives.

Wherever the infra-ordinary is taken away, wherever civilians are targeted, not only in Paris, Perec's manifesto rings true. “Question your teaspoons,” he urges us. “What is there under your wallpaper?” he asks. Perec's parents were killed in the Second World War, his father in the army, his mother in a concentration camp. He had firsthand experience of the eruption of evil into the everyday, so while in some ways An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris is a comically Parisian text—oh, the French and their wine at lunch—on some level, it is the diary of an orphaned child who can never accept that the world is the way it is. Why is the world put together this way? This si parisienne elevation of the ordinary into something compelling knows that in its peripheral vision lurks the menace of evil, and purposefully, radically chooses to focus, instead, on the fabric of peace.

As I weave and dodge my way through the tunnels at République, changing from the line 11 to the line 8, overtaking the unhurried or inhibited, I notice a man walking in the opposite direction from a ways off, holding his hand up above his head, in the form of a peace sign.

Epilogue

Wednesday 03/17/21

It's taken me a few years to consider these notes as a book, instead of—I don't know, notes toward an essay, or just some observations on my phone. Something about being yanked out of the public sphere, and resituated, inescapably, in the private sphere, made me want to revisit this text, which is so steeped in the outside world, and to think about whether it might take a more public shape.

Maybe it was the way we all—well, the writers among us anyway— responded by writing up our lockdown diaries, a form that is a close cousin to this bus diary. But mainly I was nostalgic, I think— weren't we, aren't we, all—for public transport in all its fleshy reality, for the days of sharing space and air with strangers. It seems incredible that it was ever what we did; it seems incredible, equally, that it no longer is. How long will it be until we don't have to wear masks? Until we no longer flinch when someone gets a little too close to us?

Current events in France also brought me back to this book. In the fall of 2020, the Charlie Hebdo trials began in Paris, and with them, the violence returned, extreme barbarism igniting a culture war in which the Republican value of laïcité (secularism) clashed with a growing social justice movement. These events, in the middle of a devastating pandemic itself following on from a year of Gilet jaunes protests and massive strikes, have combined to make it a very trying time to live in Paris. And I find myself wondering whether the unity that the Charlie Hebdo demonstrations tapped into is still there.

Despite our political differences, we marched together in January 2015 because it felt healing to be together, in such large numbers, in public. At so many points in our modern history, Parisians have banded together against a perceived common enemy, from the revolutions of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, to the Commune, to the Front Populaire, the Liberation, May 1968, and the riots of 1995. I'd like to think that we are bound by this history; that we are included in its collective, no matter where we're from or when we got there. That the moments of history which shatter our everyday are moments to redefine our togetherness.

The rest of the time, we're engrossed in our phones, same as anyone else, anywhere else.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you to the following people who helped make this book possible in one way or another, whether they knew it or not:

Amanda Dennis, Hedi El Kholti, Seb Emina, Annie Ernaux, Ben Hackbarth, Heidi Julavits, Chris Kraus, Stephanie La Cava, Deborah Levy, Sarah Manguso, Željka Marosevic, Cécile Menon, Georges Perec, Derek Ryan, Ileene Smith, Joanna Walsh, Alba Ziegler-Bailey, my parents, my sister, and all my anonymous fellow bus-riding Parisians.

Some parts of the final essa

y were previously published on Literary Hub, so thank you to Jonny Diamond, Michele Filgate for putting me in touch with Jonny, and John Freeman.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lauren Elkin's last book, Flâneuse: Women Walk the City, was a finalist for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay, a New York Times Notable Book of 2017, and a Radio 4 Book of the Week. After twenty years in Paris, she now lives in London.

'

No. 91/92

No. 91/92 Flâneuse

Flâneuse